By Kim Newman

Give me a hansom cab, a magnifying glass, a diabolical mystery, a deerstalker, a rattled-off deduction and Dr Watson being baffled, and I’m usually happy. I enjoy most Sherlock Holmes films – with the exception of the Peter Cook and Dudley Moore version of The Hound of the Baskervilles and the likes of Sherlock Homie: The Ass Detective, of course – but here I select my particular favourites, highlighting slightly off-the-beaten-track efforts.

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939)

There had been Holmes films since the dawn of cinema, and even whole series of silent and talkie films – including a 1922 super-production with John Barrymore, the Robert Downey Jr of the era – but it wasn’t until 1939 that the movies noticed that a) Holmes and Watson were a great double act (Watson is surprisingly downplayed in many earlier films, which derive from the William Gillette play in which a narrator isn’t needed) and b) the true era of Holmesian adventure is the 1890s (all previous Holmes films have contemporary settings).

There had been Holmes films since the dawn of cinema, and even whole series of silent and talkie films – including a 1922 super-production with John Barrymore, the Robert Downey Jr of the era – but it wasn’t until 1939 that the movies noticed that a) Holmes and Watson were a great double act (Watson is surprisingly downplayed in many earlier films, which derive from the William Gillette play in which a narrator isn’t needed) and b) the true era of Holmesian adventure is the 1890s (all previous Holmes films have contemporary settings).

This is a follow-up to a version of The Hound of the Baskervilles, which introduced Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce as Holmes and Watson, and comes up with a genuinely satisfying mystery for the sleuth to solve, pitting him against George Zucco as one of the screen’s best Moriartys. In an ingenious premise, Moriarty wants to steal the crown jewels and gets Holmes off his tail by presenting the detective with an absurdly juicy case of an imperilled heroine (Ida Lupino) stalked by a limping gaucho. Many Holmes movies feature disguise scenes the audience instantly sees through, but this (spoiler!) has one that first-timers don’t spot as a music hall artiste belting out ‘I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside’ in what seems to be a bit of cheery cockney colour pulls off the ‘tache and fake nose to reveal the hawklike Rathbone.

The Pearl of Death (1944)

Rathbone and Bruce continued with the characters on radio and in a series of films with 1940s settings – oddly, Universal made a fuss about this updating as if almost all earlier Holmes movies hadn’t taken this route. The first few entries pit Holmes against Nazis (even Moriarty was in with Hitler, the swine!) but then Universal, the go-to studio for horror films, started pitting Holmes and Watson against more fiendish menaces in old dark house mysteries. All these are wonderful – I could almost as easily have picked The Spider Woman, The Scarlet Claw or The House of Fear – but Pearl of Death, derived from ‘The Six Napoleons’ is an especial gem.

Rathbone and Bruce continued with the characters on radio and in a series of films with 1940s settings – oddly, Universal made a fuss about this updating as if almost all earlier Holmes movies hadn’t taken this route. The first few entries pit Holmes against Nazis (even Moriarty was in with Hitler, the swine!) but then Universal, the go-to studio for horror films, started pitting Holmes and Watson against more fiendish menaces in old dark house mysteries. All these are wonderful – I could almost as easily have picked The Spider Woman, The Scarlet Claw or The House of Fear – but Pearl of Death, derived from ‘The Six Napoleons’ is an especial gem.

Here, Holmes gets a terrific array of menaces, as he pits his mastery of disguise against two jewel thieves (Miles Mander, Evelyn Ankers) with an equal penchant for dressing up and putting on voices – at one point, Rathbone even does a very good vocal impersonation of Mander – plus the Hoxton Creeper, a spine-snapping maniac portrayed by the unforgettable-looking Rondo Hatton with his pulled taffy face and porkpie hat. Hatton spun off his own little series of Creeper pictures, but he’s at his best in this. Even the weakest of the Universal Holmeses are endlessly rewatchable.

The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959)

Having reinvented British horror in 1957 with The Curse of Frankenstein, Hammer Films swiftly had house director Terence Fisher and new-minted stars Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee knock out versions of Dracula, The Mummy and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s spookiest Sherlock Holmes tale. Like other early Hammer horrors, Hound is a splendidly full-blooded period melodrama, richly-produced (it was the first Holmes movie in colour), gorgeously-costumed and incisively acted by a top-flight British cast.

Having reinvented British horror in 1957 with The Curse of Frankenstein, Hammer Films swiftly had house director Terence Fisher and new-minted stars Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee knock out versions of Dracula, The Mummy and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s spookiest Sherlock Holmes tale. Like other early Hammer horrors, Hound is a splendidly full-blooded period melodrama, richly-produced (it was the first Holmes movie in colour), gorgeously-costumed and incisively acted by a top-flight British cast.

Peter Cushing’s brisk, twinkling Holmes (less fussy than in his later television takes on the role) and Andre Morell’s non-befuddled, resourceful Watson broke from the readings of the roles Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce had established twenty years earlier, opening the way for later revisions and reimaginings of the great detective and his sidekick. Christopher Lee would seem to be stuck with the stooge role as the imperilled Sir Henry, paralysed with fear as a tarantula crawls up his arm, but actually gets more screen time and more emotional range than in his higher-profile monster roles.

Hammer litter the supporting cast with wonderful British eccentrics like Miles Malleson as a dotty Bishop, John le Mesurier as the sinister butler of Baskerville Hall and Francis de Wolfe as a glowering suspect, while finding room for the studio’s traditional smouldering continental cleavage in the person of barefoot Dartmoor girl Marla Landi. Purists might object to the script’s deviation from the novel – Hammer even dare to change the identity of the ultimate villain – but Hound has been done so many times that this version has an intriguing capacity to surprise.

Bees Saal Baad (1962)

Though it omits to credit for Arthur Conan Doyle, this Bollywood box office hit is a fairly close adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles, with the setting shifted from Dartmoor to rural India (complete with a sucking swamp) and an apparent female ghost subbing for the Hound of Hell. All the familiar characters are represented: Dr Watson is pith-helmeted, moustached amateur detective bumbler Gopichand (Asit Sen), Sir Henry is handsome aristocratic hero Kumar Singh (Biswajeet) and Holmes is official Detective Tripathi (Sajjan), who spends the film lurking suspiciously as he hops about on crutches pretending to be a rural character, before a big reveal which comes when Gopichand accuses him of being the killer, only for the stalwart to throw away his crutches and accept the salutes of his fellow policemen.

Though it omits to credit for Arthur Conan Doyle, this Bollywood box office hit is a fairly close adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles, with the setting shifted from Dartmoor to rural India (complete with a sucking swamp) and an apparent female ghost subbing for the Hound of Hell. All the familiar characters are represented: Dr Watson is pith-helmeted, moustached amateur detective bumbler Gopichand (Asit Sen), Sir Henry is handsome aristocratic hero Kumar Singh (Biswajeet) and Holmes is official Detective Tripathi (Sajjan), who spends the film lurking suspiciously as he hops about on crutches pretending to be a rural character, before a big reveal which comes when Gopichand accuses him of being the killer, only for the stalwart to throw away his crutches and accept the salutes of his fellow policemen.

Like many Bollywood films, it has to fit into several genres to provide a full evening’s entertainment so at least as much time is spent on the extended flirtation, romance and complications between Kumar and the villain’s daughter. All the musical numbers belong to the love story side of the film, and the mystery has to stop sometimes to get comedy bits in from Gopichand. Director Biren Nag had obviously seen the Hammer Films Hound of the Baskervilles, since the scene in which Gopichand steps in quicksand and is hauled out by Ramlal is virtually identical to Terence Fisher’s staging of the same sequence.

For long-time Holmes fan, there’s the repeated thrill of the familiar in a strange context: the flashback pursuit and abuse of the innocent girl, the lamp waved from the palace to alert the fugitive on the moor, the local doctor’s suspicious involvement in the succession at the manor, the detective pretending to leave by train to use the hero as bait to trap the killer. Nag is at his best in the few horror movie moments – the initial stalking of the uncle by the long-nailed killer, the final unmasking of the furious Ramlal as the fake ghost, sundry skulkings in gloomy locales.

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970)

‘We all have our occasional failures,’ admits Billy Wilder’s wry Sherlock Holmes (Robert Stephens). ‘Fortunately, Dr Watson never writes about mine.’ Wilder originally shot an epic-length Valentine to Victorian adventure, but the film was tragically taken from him and mutilated by the wholesale lopping of entire episodes, including ‘The Case of the Upside-Down Room’. What remains is so wonderful that those 1970 studio philistines should be sought out in retirement homes and cemetery plots and shouted at.

‘We all have our occasional failures,’ admits Billy Wilder’s wry Sherlock Holmes (Robert Stephens). ‘Fortunately, Dr Watson never writes about mine.’ Wilder originally shot an epic-length Valentine to Victorian adventure, but the film was tragically taken from him and mutilated by the wholesale lopping of entire episodes, including ‘The Case of the Upside-Down Room’. What remains is so wonderful that those 1970 studio philistines should be sought out in retirement homes and cemetery plots and shouted at.

A loving recreation of the world of Arthur Conan Doyle, this has a Holmes whose deductions and repartee are tossed off with a touch of Wilde and who constantly complains that Watson’s accounts of his work grossly misrepresent him (‘he has saddled me with this improbable outfit which the public now expects me to wear!’). To Watson’s fury and discomfort, Holmes even pretends to be gay in order to see off a ballerina who wants him to father her child (‘Tchaikowsky is not an isolated case’), though we learn he is really a cynical romantic, dangerously prone to be fooled by an amnesiac beauty (Genevieve Page) fished out of the Thames.

The fiendish plot takes in bleached canaries, missing midgets, sinister Trappists, the Loch Ness Monster, and Queen Victoria. Also: sumptuous period settings, a seductive Miklos Rosza score, and great character work from Colin Blakely (an exasperated Dr Watson), Irene Handl (a sarcastic Mrs Hudson) and Christopher Lee (pompous brother Mycroft). A true evocation of the spirit of the Strand Magazine, this is the best Holmes movie ever made and sorely underrated in the Wilder canon.

They Might Be Giants (1971)

A whimsical, magical picture – maybe too soft-centered for its era – which is a tribute to a bygone era of intrepid, selfless heroism. Director Anthony Harvey and writer James Goldman had just made the acid, cynical historical drama The Lion in Winter, but here go for a more autumnal mood – like Harold and Maude or The King of Hearts, it’s the sort of small, quirky, sentimental-but-strange picture which sticks in the mind and is quite likely to be cherished as an offbeat favourite.

A whimsical, magical picture – maybe too soft-centered for its era – which is a tribute to a bygone era of intrepid, selfless heroism. Director Anthony Harvey and writer James Goldman had just made the acid, cynical historical drama The Lion in Winter, but here go for a more autumnal mood – like Harold and Maude or The King of Hearts, it’s the sort of small, quirky, sentimental-but-strange picture which sticks in the mind and is quite likely to be cherished as an offbeat favourite.

In contemporary New York, neurotic psychiatrist Dr Mildred Watson (Joanne Woodward) is called in to treat Justin Playfair (George C. Scott), a retired judge who insists that he’s Sherlock Holmes and dresses the part. He naturally responds to her name and tries to enlist her in his feud with the unseen Moriarty, whom he claims is behind every crime in the city. Not only is she is unable to shake him from his delusion but she starts to join in because, after all, his deductions are on the money and his embarrassing antics do genuinely make him an expert crime-fighter.

A later TV movie, The Return of the World’s Greatest Detective, used the same premise, but without the skill of Woodward and Scott, who show the glimpses of pain behind the comedy, the soufflé collapsed. Yes, the band did take their name from the film – the title refers to Don Quixote’s windmills.

Murder By Decree (1979)

In 1888, Sherlock Holmes (Christopher Plummer) and Dr Watson (James Mason) are called to investigate the Jack the Ripper murders, and uncover a conspiracy that extends from the gutters of Whitechapel to ‘the highest in the land’. The Hughes Brothers’ From Hell is a de facto remake of this Sherlock Holmes movie, which proposes exactly the same far-fetched, later-discredited ‘solution’ to the mystery of Jack the Ripper – involving a Masonic conspiracy, the Queen’s own surgeon and a hit-list of East End harlots who have their throats cut to conceal a Royal scandal.

In 1888, Sherlock Holmes (Christopher Plummer) and Dr Watson (James Mason) are called to investigate the Jack the Ripper murders, and uncover a conspiracy that extends from the gutters of Whitechapel to ‘the highest in the land’. The Hughes Brothers’ From Hell is a de facto remake of this Sherlock Holmes movie, which proposes exactly the same far-fetched, later-discredited ‘solution’ to the mystery of Jack the Ripper – involving a Masonic conspiracy, the Queen’s own surgeon and a hit-list of East End harlots who have their throats cut to conceal a Royal scandal.

This more obviously fictional earlier draft is the better bet, with a well-constructed screenplay from John Hopkins and a very fine Holmes and Watson teaming from Christopher Plummer and James Mason. Mason makes a lot out of a tiny little scene about eating peas and provides a human centre for a fairly cynical tale, while Plummer is a more impassioned Sherlock than usual, dryly sorting through clues but appalled by the truths he uncovers and even, at one point, moved to tears.

It has the expected Ripper business of prowling through foggy alleyways and riotous behaviour in Whitechapel gin-mills, but ventures into unusual areas with a series of guest star turns from David Hemmings as a Scotland Yard inspector who turns out to be a radical out to use the killings to inspire a revolution, Donald Sutherland as an enormously-whiskered psychic who claims to have an insight into the case, John Gielgud as the smug Prime Minister who decides to institute a Watergate-style cover-up to maintain public order and (especially) Genevieve Bujold as a former Royal mistress unjustly confined in an insane asylum. An earlier, similar effort – which even has Frank Finlay in the same role (Inspector Lestrade) – is A Study in Terror (1964), which is more lurid but nevertheless spirited fun.

Zero Effect (1998)

This prefigures the Peter Moffat/Mark Gatiss Sherlock in that it tries to imagine what Holmes and Watson would be like if the characters were created now – though the story is closely derived from Doyle’s ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’, it comes up with fresh versions of the well-loved duo. Steve Arlo (Ben Stiller), a long-suffering lawyer, works for the neurotic, eccentric, brilliant private investigator Daryl Zero (Bill Pullman), who is hired by tycoon Gregory Stark (Ryan O’Neal) to see off a blackmailing mystery woman (Kim Dickens).

This prefigures the Peter Moffat/Mark Gatiss Sherlock in that it tries to imagine what Holmes and Watson would be like if the characters were created now – though the story is closely derived from Doyle’s ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’, it comes up with fresh versions of the well-loved duo. Steve Arlo (Ben Stiller), a long-suffering lawyer, works for the neurotic, eccentric, brilliant private investigator Daryl Zero (Bill Pullman), who is hired by tycoon Gregory Stark (Ryan O’Neal) to see off a blackmailing mystery woman (Kim Dickens).

Writer-director Jake Kasdan translates the drug-using, personally distant violin virtuoso Holmes into an amphetamine-popping, neurotically withdrawn bedroom guitar-player. Like Holmes, Zero is a master of disguise (partly to submerge his own loser personality) and a whizz at deduction, with a repertoire of suggestive-sounding past cases to name-drop, like The Case of the Hired Gun Who Made Way Too Many Mistakes and The Case of the Guy Who Lied About His Age.

Pullman, one of American cinema’s most valuable players, is outstanding as the flawed genius, working in a sense of tragedy that makes this more than just a clever exercise. A rare film to satisfy fans of classical mysteries (the illustrated deductions are perfect) and quirky-sad comedy-drama. Alan Cumming took over the role in a TV pilot which sadly didn’t lead to a series.

Murder Rooms: The Dark Beginnings of Sherlock Holmes (2000)

Based on the well-known fact that Arthur Conan Doyle’s inspiration in creating the character of Sherlock Holmes was deduction-happy Edinburgh doctor Joseph Bell, David Pirie’s clever teleplay has student Doyle (Robin Laing) serving as Watson to Bell (Richardson) as he investigates a series of odd crimes. The case is a complex puzzle of the Holmes variety, with a series of crimes which seem to follow the course of a psalm, odd clues like neat piles of coins found by the victims, prefigurings of later Holmes cases like a pair of ears delivered in a cardboard box, set-piece gruesomeness like a room completely drenched in blood (sheep’s, as it turns out) and a scandal involving the marriage of the university’s high-born but rotten patron (Charles Dance), who not only gives his wife syphilis and threatens to have her put in an asylum on the grounds of moral corruption but also plots to have her poisoned.

Based on the well-known fact that Arthur Conan Doyle’s inspiration in creating the character of Sherlock Holmes was deduction-happy Edinburgh doctor Joseph Bell, David Pirie’s clever teleplay has student Doyle (Robin Laing) serving as Watson to Bell (Richardson) as he investigates a series of odd crimes. The case is a complex puzzle of the Holmes variety, with a series of crimes which seem to follow the course of a psalm, odd clues like neat piles of coins found by the victims, prefigurings of later Holmes cases like a pair of ears delivered in a cardboard box, set-piece gruesomeness like a room completely drenched in blood (sheep’s, as it turns out) and a scandal involving the marriage of the university’s high-born but rotten patron (Charles Dance), who not only gives his wife syphilis and threatens to have her put in an asylum on the grounds of moral corruption but also plots to have her poisoned.

Historical material is interleaved with the crimes, so young Doyle has a romance with a medical student (the winning Dolly Wells) during the controversy over whether women should be allowed to study to become doctors. We see a few famous Bell/Holmes anecdotes (flogging a corpse, deducing a man’s history) and the incident of Holmes deducing the decline of Watson’s brother by examining his watch is transmuted into Bell’s assessment of the character of Doyle’s demented father.

The primary villain of the piece quotes Poe on the imp of the perverse and enjoys poisoning prostitutes — a pure psychopath beyond the reach of Bell’s understanding, he shows the limits of deductive reason as a criminological tool. The suggestion is that Doyle’s fictions were intended to contain such monsters in understandable form, and the wrap-up looks to the future and the rise of meaningless crime. A later TV series, with Laing replaced by Charles Edwards, is also interesting, and Pirie wrote a series of novels similarly developing the characters and their world.

Case of Evil (aka Sherlock) (2002)

Well before Guy Ritchie had set out to reimagine Holmes and Watson as a modern movie action hero, this interesting TV movie took a similar approach, though some aspects are calculatedly revisionary – as when Holmes has a threesome with a pair of actresses who are essentially 19th Century detection groupies. It opens with Holmes (James D’Arcy), working for a mysterious lady (Gabrielle Anwar), gunning down blackmailer Moriarty, who does the familiar act of falling into a sewer so the body isn’t found.

Well before Guy Ritchie had set out to reimagine Holmes and Watson as a modern movie action hero, this interesting TV movie took a similar approach, though some aspects are calculatedly revisionary – as when Holmes has a threesome with a pair of actresses who are essentially 19th Century detection groupies. It opens with Holmes (James D’Arcy), working for a mysterious lady (Gabrielle Anwar), gunning down blackmailer Moriarty, who does the familiar act of falling into a sewer so the body isn’t found.

In this version, Watson (Roger Morlidge) is a working coroner (and two-fisted Cambridge boxing blue) who gets together with Holmes as they work a case, a series of mystery deaths among opium-sellers in London. Mycroft (Richard E. Grant) is here a broken man, sedentary because Moriarty drugged and brutally operated on his legs, giving Sherlock, who witnessed this atrocity as a child, a lifelong need for vengeance. Moriarty (Vincent d’Onofrio, doing an effective James Mason voice) is working to transform the illegal drugs market, refining opium into what we recognise as heroin, though he hasn’t yet come up with a ‘street name’ and toys with the term ‘drug baron’ as opposed to Sherlock’s suggestion ‘dealer’.

In a variation on French Connection II, Holmes falls into the villain’s hands and is used as a test subject for the new product, then has to be weaned off it by Watson. The finale is a shoot-out siege in London, intended to feel like the first gangster battle, followed by a traditional swordfight inside Big Ben which ends up with Moriarty taking yet another fatal fall. Rather neater is the running gag about a sleazy reporter (Peter-Hugo Daly) who pesters Holmes and feeds off him for headlines, prompting the detective to muse that his posterity had better be taken care of by Watson, who amends his own case-book by putting in Holmes’ name.

D’Arcy perhaps overdoes the twitchy neuraesthenia but settles nicely, and there’s a satisfying finish as Holmes takes a deerstalker sent him by his mad aunt Agatha and a pipe Watson has given him because he thinks cigarettes will be banned by law before opium or cocaine and becomes the familiar silhouette for a photograph that seals him in history.

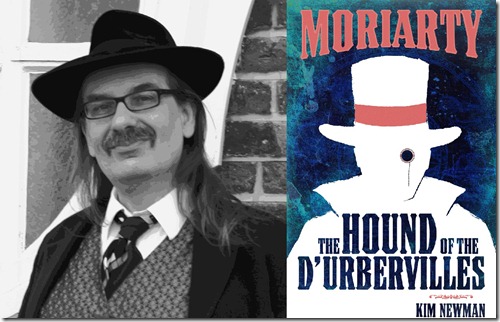

Kim Newman is an English journalist, film critic (Empire Magazine) and award-winning author (the Bram Stoker Award, the International Horror Guild Award, the BSFA award). His latest novel, Professor Moriaty: Hound of the D’Urbevilles was released on the 23rd September 2011 and is available now from all good book shops (Titan Books, RRP £7.99).

Kim Newman is an English journalist, film critic (Empire Magazine) and award-winning author (the Bram Stoker Award, the International Horror Guild Award, the BSFA award). His latest novel, Professor Moriaty: Hound of the D’Urbevilles was released on the 23rd September 2011 and is available now from all good book shops (Titan Books, RRP £7.99).

—

Alternative Offerings:

I absolutely love Sherlock Holmes!

But you missed all of my favourites.

While it might break canon I loved Young Sherlock Holmes.

And if we allow similar/obviously taken a lot of inspiration from/ recommendations for Sherlock lovers then I absolutely have to mention The Name of the Rose.

Cheers Kim

Not familiar with Zero Effect or a Case of Evil, must look them out.